- GCaM

- Posts

- Loading... Regime Change in Venezuela

Loading... Regime Change in Venezuela

Dear all,

We welcome you to the Greater Caribbean Monitor (GCaM).

In this issue, you will find:

Maduro will likely fall; the question is how

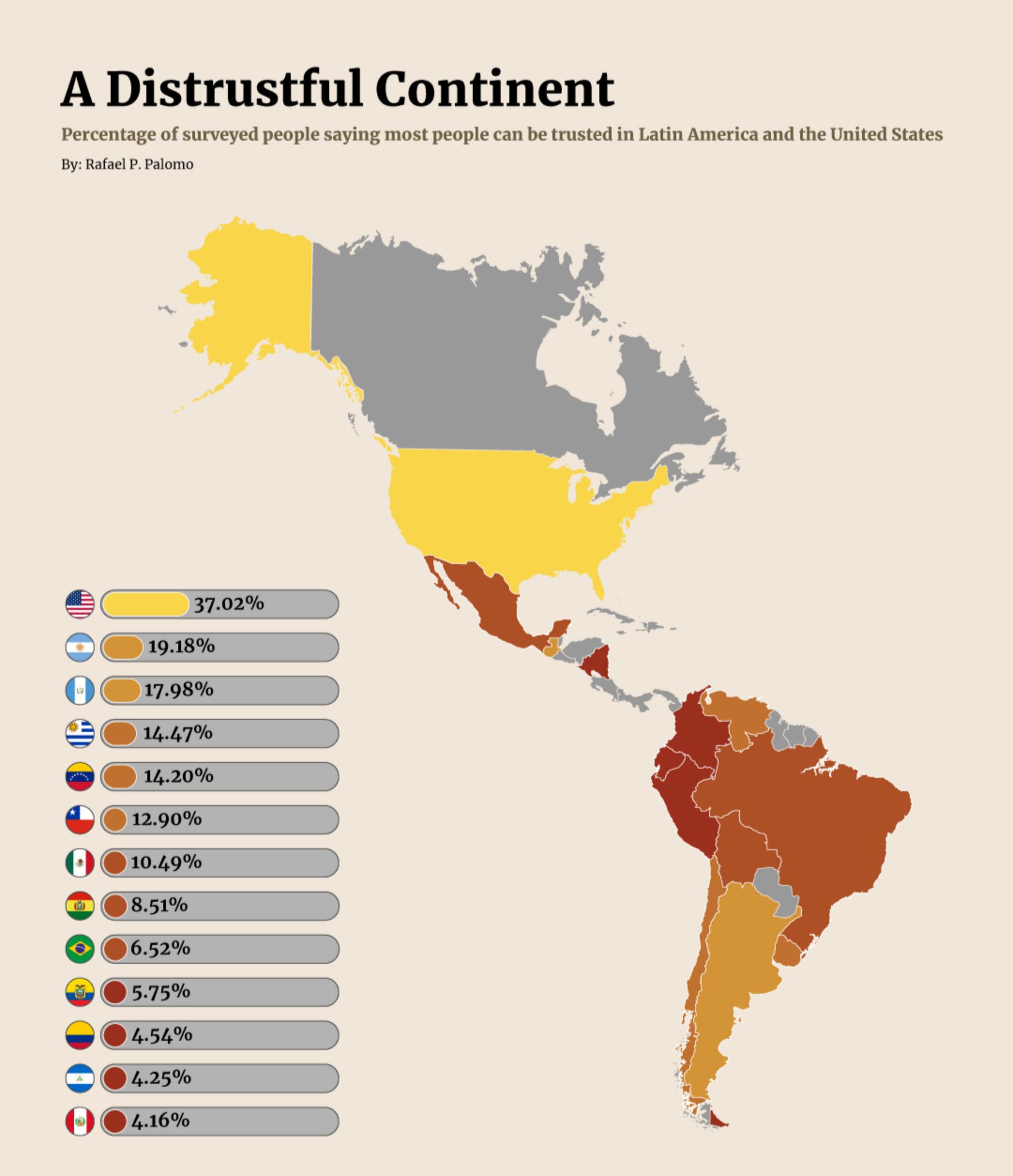

A Distrustful Continent

What We’re Watching

As always, please feel free to share GCaM with your friends and colleagues.

If you’ve been forwarded this newsletter, you may click here to subscribe.

Best,

Rafael P. Palomo, GCaM editor

Maduro will likely fall; the question is how

700 words | 4 minutes reading time

The escalation is no longer hypothetical. President Donald Trump has now approved covert CIA operations inside Venezuela, a decisive shift from maritime interdiction to a pre-invasion “battlefield-shaping” phase.

In perspective. The New York Times reports that the authorization covers sabotage, psychological ops, cyber disruption, and clandestine pressure designed to fracture Nicolás Maduro’s inner circle. It is the most significant expansion of U.S. power in South America since Plan Colombia, but with far higher stakes.

At the same time, Trump has opened new back-channel negotiations with Caracas, which reportedly produced a stunning revelation.

Maduro privately offered to step down within a couple of years. The White House rejected the deal—suggesting Washington believes it can force a faster collapse.

The question now is no longer whether the U.S. is preparing for regime change, but how it intends to get there.

Blitzkrieg time. One of the possible routes is to force Maduro out through strength. CIA covert ops typically precede kinetic force when Washington wants to shorten a battlefield and avoid U.S. troop deployments (think Soleimani, early Afghanistan, or Panama 1989). If Trump authorizes additional strikes, beyond the ongoing naval interdictions, the likely targets include Maduro’s presidential guard, military intelligence headquarters, radar and anti-air assets, key figures linked to the Cartel de los Soles, and oil infrastructure tied to regime financing.

Maduro’s regime is vulnerable. Years of sanctions, elite factionalism, and coup-proofing paradoxically created internal redundancy that is brittle under external shock.

And unlike past U.S. interventions, none of Maduro’s allies—Cuba, Russia, China, or Iran—have both the capacity and political will to escalate against Washington.

A blitzkrieg-style strike could rapidly dismantle command-and-control, triggering defections and forcing Maduro into exile. This is the option Trump’s hawks prefer.

Through the back door. Despite his rhetoric, Maduro has tested off-ramps before, and his recent alleged offer to leave in two years reveals something important: For the first time since 2019, the regime sees an existential threat. The U.S. military buildup in the Caribbean has changed internal calculations. As José Ramón Morales Arilla notes, credible coercion makes transitional justice deals feasible.

If generals believe Washington will strike and that Russia or Cuba can’t save them, their loyalty evaporates.

This scenario resembles Noriega’s collapse in Panama, with a U.S. pressure campaign that triggers elite fragmentation, producing a negotiated exit.

For Washington, this is the cleanest scenario, but still uncertain.

Yes, but. If Maduro absorbs the shock through loyal militias, Cuban intelligence support, or asymmetric resilience, Trump risks the worst-case dilemma: to escalate into deeper conflict (risking U.S. casualties and political backlash) or settle into a long, low-intensity confrontation that drains the administration’s attention and strength.

Maduro’s ecosystem is far larger and more entrenched than past Latin American interventions.

Even decapitation strikes may not collapse the security apparatus, and the aftermath would place the burden on a fragmented Venezuelan opposition.

This is the scenario the White House fears most.

What follows. Trump is betting on sustained, targeted pressure to crack the military and force a palace split—not a full-scale U.S. invasion. Covert ops, naval pressure, and internal panic equal a calculated strategy to collapse Maduro without U.S. boots. And it may work.

Maduro’s inner circle is fractured, isolated, financially cornered, and facing a superpower openly preparing for strikes.

The fact that Maduro even floated a delayed resignation is the clearest signal yet. The regime knows time is running out.

In conclusion. The CIA greenlight marks the start of Venezuela’s most volatile phase since 2019. Trump’s pressure campaign is designed to be short, sharp, and decisive—a “gunboat diplomacy light” adapted for the post-Iraq era. The most plausible outcome is Maduro won’t fall to bombs; instead, he'll fall to fear. A negotiated exit or internal coup is now more likely than a prolonged war. Failure, however, would force Trump into a strategic corner with no good choices.

Two forces will decide the outcome: whether Washington’s covert playbook fractures the Venezuelan military or whether Maduro’s allies believe the U.S. is willing to go all the way.

For now, both the battlefield and the back channels point to the same conclusion.

Maduro has entered his final chapter; the only question is how it ends.

Trust is Latin America’s missing institution. The map tells a story the region keeps avoiding: Latin America is one of the least trusting regions on Earth.

In perspective. Outside the United States (37%), no country reaches even 20% of people who say “most people can be trusted.” Most hover near zero.

And that single number reveals more about the region’s institutional failures and economic stagnation than any ideological debate.

Why it matters. Francis Fukuyama’s argument in Trust is simple: high-trust societies build strong institutions, scale their economies, and cooperate beyond family networks. Low-trust societies don't—and stay poor. Latin America falls firmly in the second category.

Trust is the foundation that lets societies delegate authority and accept impersonal rules. When trust collapses, institutions are perceived as tools for political factions, not public goods. And often, that perception is accurate.

The causality is circular: low trust creates weak institutions, and weak institutions deepen low trust.

More in-depth. Countries at the bottom of the chart—Peru (4.16%), Nicaragua (4.25%), Colombia (4.54%), and Ecuador (5.75%)—are exactly the ones suffering chronic political instability, high corruption, and institutional breakdown. Citizens retreat into family networks and short-term strategies, the survival mechanism Fukuyama describes as familism.

In that environment, building capable states becomes nearly impossible.

Between the lines. A functioning state requires legitimacy, not just authority. When people don’t trust institutions, governments enforce compliance through force, not consent, producing brittle, easily contested orders. That dynamic shows up everywhere.

Police forces are seen as corrupt, enabling parallel criminal governance; judicial systems are perceived as politicized, weakening the rule of law; and public services become vulnerable to clientelism, undercutting human capital.

Latin America has agencies, laws, and reforms. What it lacks is the social capital that makes them credible.

Hidden in plain sight. Trust is an economic asset. High-trust countries build complex corporate structures and long-term relationships. Low-trust societies rely on small, family-based firms that struggle to scale. Latin America reflects this perfectly, with high informality, because people don’t trust the state; low investment, because property rights are insecure; weak innovation, because collaborative networks are thin; and poor regulatory compliance, because institutions lack legitimacy.

The result is a region stuck in permanent underperformance. When trust collapses, political intermediaries collapse with it.

Citizens believe only “outsiders” can fix the system, producing cycles of populism that promise ruptures but rarely build durable institutions.

In conclusion. Every major reform—anti-corruption campaigns, security strategies, democratic transitions—fails when trust is missing. Trust is not cultural decoration; it is fundamental institutional infrastructure. Rebuilding trust means establishing credible, depoliticized institutions, a consistent rule of law, accountability with real consequences, and participation from civil society and the private sector.

Until then, low trust will remain the region’s most binding constraint, and the quiet force behind its political volatility and economic stagnation.

What We’re Watching 🔎 . . .

R. Evan Ellis, Expediente Abierto

The latest brief by R. Evan Ellis exposes why Cuba is no longer a side story but the strategic hinge of Trump’s entire “America First” posture in the Caribbean. The report outlines how Havana has become a platform for extra-hemispheric adversaries—hosting Russian warships, Chinese SIGINT bases in Bejucal, Iranian delegations, and even serving as refuge for Chinese fentanyl trafficker “Brother Wang.”

For Trump’s militarized pressure on Venezuela to work, Cuba must be contained: its intelligence networks dismantled, its support to Maduro neutralized, its collaboration with Beijing and Moscow restricted. With more than one million Cubans fleeing since 2020 and the island embedded in the architecture of the Cartel de los Soles, Washington sees Havana as both a threat multiplier and a leverage point.

Ecuador Votes No to Hosting U.S. Military Base [link]

Genevieve Glatsky and José María León Cabrera, The New York Times

Ecuadorian voters delivered President Daniel Noboa a major defeat on Sunday, rejecting his proposal to authorize a foreign—effectively U.S.—military presence by 61%. The rebuke comes after months of Noboa courting Washington, from Mar-a-Lago meetings with Trump to touring potential U.S. base sites with Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem.

But analysts say the vote was less a rejection of the U.S. than of Noboa himself, amid soaring homicides, prison massacres, explosions, medicine shortages, and deadly protests over fuel cuts. After two years in office, Ecuador is on track for its most violent year on record, eroding trust in his security agenda. Noboa’s earlier political momentum has evaporated; voters now want results, not promises.