- GCaM

- Posts

- Venezuela After Maduro: a GCaM Special

Venezuela After Maduro: a GCaM Special

Dear all,

We welcome you to the Greater Caribbean Monitor (GCaM), the last of the year.

Today you are receiving a special edition of GCaM, dedicated to Venezuela, as the current moment demands. The situation, as expected, has shifted from euphoria to an uneasy and chaotic expectation—more worrying than exciting for many. Even so, the Venezuelan people still have many reasons to celebrate. These are, however, the moments in which the country’s future will be decided, and in which the way forward for a nation will be shaped—one that, while facing a long road back to normality, has spent far too many years in the grip of socialism and dysfunction to expect a smooth or gentle transition. For our part, we will continue to follow and report on developments closely.

In this issue, you will find:

The Day After Caracas: Venezuela, U.S. Power, and the Limits of Intervention

No, the U.S. is Not Obsessed With Venezuelan Oil

Rome Does Not Pay Traitors

What We’re Watching

As always, please feel free to share GCaM with your friends and colleagues. We wish you a strong start to 2026.

If you’ve been forwarded this newsletter, you may click here to subscribe.

Kind regards,

The Day After Caracas: Venezuela, U.S. Power, and the Limits of Intervention

904 words | 5 minutes reading time

A watershed moment in global order: the U.S. capture of Nicolás Maduro has created reverberations far beyond Caracas.

In perspective. The audacious operation on January 3, 2026—executed by U.S. military and special forces, resulting in Maduro’s capture and extradition to New York—was justified in Washington as a law-enforcement action against narcoterrorism and transnational crime.

Yet its impact will be measured not just in Venezuela’s uncertain streets, but in how great powers interpret the rules of intervention and influence in a fracturing international system.

What's next. The immediate question is whether this moment will catalyze a genuine transition beyond Maduro’s removal. In the aftermath of the operation, Vice President Delcy Rodríguez has been sworn in as interim president, and the U.S. administration has signaled support for a transitional period, if not direct governance.

Trump himself stated that the U.S. would “run the country until such time as we can do a safe, proper and judicious transition,” though Secretary of State Marco Rubio later walked back claims of long-term rule, emphasizing pressure and reconstruction rather than occupation.

It’s clear why Trump favored Rodríguez over María Corina Machado. Despite Machado’s long-standing opposition to Maduro, U.S. assessments reportedly shifted toward Rodríguez because she retains established ties with the military and business sectors, elements critical to stability in the short run.

Without credible control over the armed forces and elite institutions, a leader risks presiding over fragmentation rather than transition.

Between the lines. Yet Rodríguez’s interim status is a double-edged sword. On one hand, her constitutional continuity offers a veneer of legal legitimacy and continuity of state functions, which the U.S. and regional governments can engage with. On the other hand, her roots in the Maduro era mean that genuine systemic change, dismantling clientelist networks, rebuilding institutions, and arranging free elections, is far from guaranteed.

Experts warn that even after Maduro’s ouster, the prospects for comprehensive regime change are bleak, hinging more on internal bargaining among power brokers than on Washington’s actions.

In the coming months, Venezuela may see a managed transition with phased reforms, prisoner releases, and diplomatic normalization—the U.S. and Venezuelan technical teams are already discussing reopening diplomatic channels.

Whether this evolves into true democratic renewal or a controlled reshuffling of elites remains the central question. The outcome will shape not only Venezuela’s future but also the credibility of U.S. intervention as a tool for political transformation.

Regional echoes. Around the world, responses to the U.S. action have split sharply along geopolitical lines. Many Western governments and civil society voices have expressed legal concerns, questioning the legality of a unilateral military operation on sovereign territory. United Nations experts warned that the strikes threaten international law and could erode norms that have underpinned state sovereignty since World War II.

Mexico’s President Claudia Sheinbaum publicly rejected the intervention, reaffirming opposition to extraterritorial military action.

In Caracas and allied capitals, the operation has been framed as a violation of national sovereignty and a dangerous precedent.

Cuban and other allies of the former regime decried the U.S. strikes, while the Venezuelan Supreme Tribunal swiftly declared Rodríguez’s interim leadership, bypassing full elections.

Beyond the hemisphere. In this context, the fear that U.S. action could legitimize similar interventions by other great powers in their spheres of influence—notably, China on Taiwan or Russia on Ukraine—merits scrutiny. But the logic underpinning the Venezuela case suggests the opposite. Beijing and Moscow have publicly condemned the U.S. operation as aggressive and illegal, using it in their propaganda to warn of Western interventionism.

Russian officials and state media have invoked principles of sovereignty and non-interference, seeking to delegitimize U.S. influence globally.

Likewise, China’s foreign ministry has highlighted the danger of using force to settle political disputes, framing U.S. action as a threat to international stability.

Yes, but. If anything, the Venezuela intervention sends a different message: powerful states make their own rules, but not all interventions are equal nor equally replicable. The United States—by virtue of its unmatched global reach, military logistics, and legal apparatus—is signaling that it believes only a superpower with global bases, allies, and command structures can undertake such operations and seek to shape outcomes.

This is less a model for others to emulate and more an assertion of U.S. exceptional capacity.

For China, whose strategic doctrine emphasizes economic leverage and incremental military posture, and for Russia, which lacks the same expeditionary reach, the policy lessons are limited.

In both cases, opportunistic narratives will likely flourish, but actual operational parallels are constrained by capacity and risk profiles.

In conclusion. The underlying signal from Washington is not a multipolar permission slip for intervention. U.S. policymakers are betting that a decisive display of force under the banner of law enforcement and counter-narcotics can consolidate influence regionally while reinforcing the perception that Washington remains the dominant security actor in the Western Hemisphere. This may alienate partners wary of unilateralism and challenge the normative frameworks that underpin international cooperation.

At the same time, it reinforces U.S. deterrence credibility in contexts where adversaries test thresholds of action. Ultimately, how the Venezuela intervention shapes global norms hinges on follow-through.

Whether the transition results in accountability, restoration of democratic processes, and respectful engagement with international institutions or whether it becomes another footnote in a new era of great-power assertiveness.

In a world where power and legitimacy are increasingly decoupled, this moment may be less about legitimizing interventionism and more about who gets to define its limits.

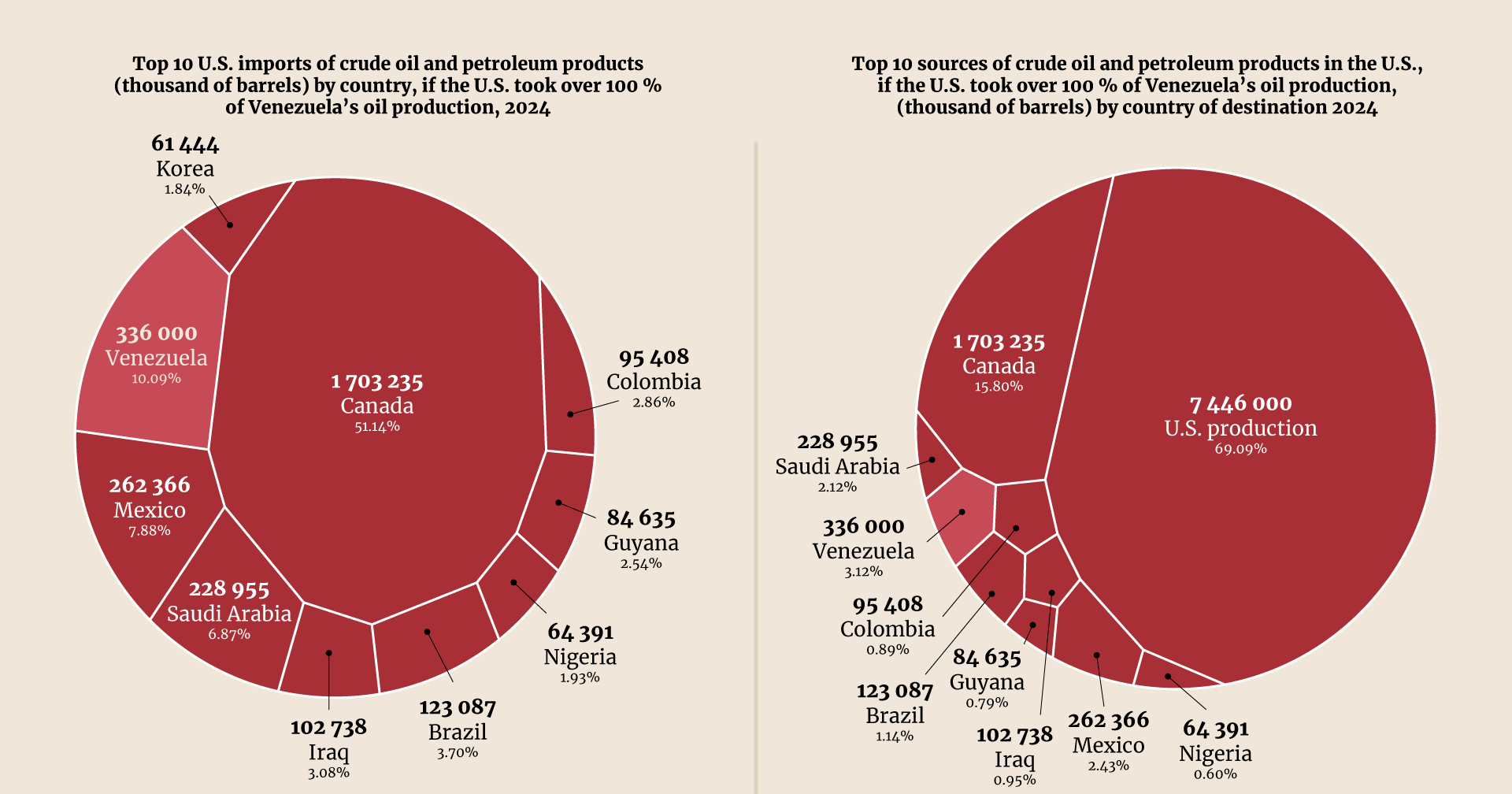

The usual narrative. The idea that the United States would intervene in Venezuela primarily to seize its oil resurfaces every time tensions spike between Washington and Caracas. It is a familiar narrative, politically useful for the chavista movement and widely repeated across sympathetic media ecosystems. But when tested against basic data on U.S. energy consumption, the argument collapses. The numbers tell a far less dramatic story, one in which Venezuelan oil is, at best, marginal to U.S. energy security.

In 2024, Venezuelan crude and petroleum products accounted for roughly 3 percent of total U.S. imports and about 1.2 percent of total U.S. consumption. Even before sanctions hardened, Venezuela had already lost relevance as a supplier.

The United States today covers close to 70 percent of its oil consumption through domestic production, with Canada supplying the overwhelming majority of imports. Mexico, Saudi Arabia, Brazil, and Iraq all matter more to the U.S. energy balance than Venezuela does.

From a purely economic perspective, removing Venezuelan oil from global markets barely registers in U.S. energy planning.

The real picture. To stress-test the argument, we ran a hypothetical scenario: what if the United States were to take control of all of Venezuela’s oil production and redirect it entirely toward U.S. consumption? Even under this extreme and unrealistic assumption, Venezuelan oil would still represent only a small fraction of U.S. supply.

Domestic production would remain dominant, Canada would still anchor imports, and Venezuela would move from marginal to mildly relevant—but nowhere near decisive.

In other words, even a full takeover of Venezuelan output would not materially alter U.S. energy security. If oil were the motive, the payoff would be remarkably underwhelming.

In this scenario, while Venezuela would become the second biggest source of oil imports, it would still represent a 3.12 % of all oil consumption. One does not risk a military confrontation for such an amount—especially when the U.S. remains the biggest oil producer in the world.

Between the lines. This is why the “oil obsession” narrative fails. The strategic incentives simply do not align. The United States does not need Venezuelan oil to stabilize prices, ensure supply, or maintain industrial capacity. Shale production, diversified imports, and strategic reserves already cover those bases. What Washington does face, however, is a persistent security problem emanating from Caracas—one that oil revenues help finance but do not define.

The real driver is the criminalized architecture of the chavista state. Over two decades, Venezuela evolved into a hub linking narcotrafficking networks, sanctioned financial channels, and hostile foreign actors.

The regime’s ties to Russia, China, Iran, and Hezbollah are not rhetorical flourishes, but operational relationships that extend into intelligence cooperation, sanctions evasion, and regional destabilization.

Oil matters here only insofar as it provides cash flow for these networks—not as a strategic commodity the U.S. lacks.

In addition. Venezuela’s role as a sponsor and enabler of other authoritarian regimes also matters. Support for Nicaragua and Cuba, coordination with transnational criminal groups, and the use of migration and energy leverage as political tools place Caracas squarely within a broader challenge to U.S. influence in the hemisphere. From Washington’s perspective, this is not about barrels; it is about containment of an illicit state aligned with U.S. adversaries inside the Western Hemisphere.

Seen through this lens, the fixation on oil looks less like analysis and more like misdirection.

The data show that Venezuelan crude is economically insignificant to the United States, even under hypothetical scenarios designed to exaggerate its importance.

What is significant is the regime’s function as a geopolitical and criminal node. That—not oil—is why Venezuela remains on Washington’s strategic radar.

Rome Does Not Pay Traitors

629 words | 3 minutes reading time

Venezuela’s latest political reconfiguration is less a democratic breakthrough than a case study in how the U.S. now manages power. The displacement of María Corina Machado and the elevation of Delcy Rodríguez reflect a shift toward controlled stabilization, where usefulness is measured by governability.

Behind this move lies a broader doctrine, shaped by Marco Rubio’s operations, that treats Latin America as a testing ground for new rules of coercion and unpredictability.

How it works. Marco Rubio has treated Latin America not as a peripheral theater, but as a laboratory for rewriting the rules of the global order, using the region to test a more coercive, less predictable form of U.S. power.

Rubio has systematically pushed the concept of narcoterrorism to collapse distinctions between criminal networks, authoritarian governments, and national sovereignty. By reframing regimes like Venezuela’s as hybrid threats, he dilutes the protections of classical international law and destabilizes the previous equilibrium that separated crime control from acts of war.

In his advisory role and public alignment with Trump, Rubio has consistently argued for raising the stakes: moving from legal commercial actions to the credible threat of force. The objective is not immediate invasion, but permanent escalation dominance, forcing adversaries to operate under constant risk.

The previous order made U.S. behavior legible and therefore containable. Rubio’s framework replaces predictability with uncertainty. States may not know whether their sovereignty is imminently at risk, but they do know that if Washington decides it is, a strike will come.

The indispensable. Rome rewards those who can govern aftermaths, not those capable of burning bridges. María Corina Machado was instrumental during the phase of maximum pressure: delegitimizing the regime, hardening external positions, and embodying a discourse of total rupture. That made her valuable as a catalyst for instability, not as an architect of transition.

As external actors move from seeking collapse to prioritizing containment, predictability, and normalization, Machado’s absolutist posture becomes a liability. Stabilization demands negotiable figures who can manage continuity and guarantees—traits fundamentally at odds with her discourse and legitimacy.

The U.S. intervention logic resembled a decapitation strike, not a full-scale invasion. That approach requires engaging deeply embedded elites and keeping the state apparatus operational under new management.

Machado’s fierce opposition to those structures leaves her without leverage to control or reorder them.

Between the lines. Delcy Rodríguez emerges as a central figure in a transition logic focused not on rupture, but on managed continuity under new constraints, aligning with U.S. priorities of stability, control, and predictability.

Rodríguez’s authority over PDVSA and her senior roles under Maduro place her at the core of the state’s economic and institutional machinery. For Washington, this is decisive: energy flows, fiscal control, and bureaucratic obedience cannot be rebuilt from scratch without risking collapse.

Unlike opposition figures defined by confrontation, Rodríguez can negotiate with military, security, and economic elites because she is one of them. The U.S. strategy aims to replace leadership at the top while keeping the structure functional.

From the American perspective, it is irrelevant whether Rodríguez is a democratic symbol. Her value lies in operational capacity: predictability, transactional competence, and the ability to deliver compliance on oil, sanctions relief, and security guarantees.

The near future. Venezuela’s immediate outlook points less toward recovery than toward managed survival within a reordered geopolitical logic. State capacity remains critically weak: public services barely function for the population, let alone for the institutional guarantees required to attract long-term capital.

Venezuela also faces one of the most complex debt-refinancing processes in modern history, combining sovereign default, PDVSA liabilities, arbitration awards, and sanctions entanglements.

Geopolitically, China—now increasingly dominant in wind, solar, and energy storage—will not depend on Venezuelan oil within a decade. Russia has no urgent stake, as the country lies outside its immediate security perimeter.

Venezuela thus functions less as a strategic energy asset than as a demonstration strike: a signal of what the U.S. is willing to do to reshape regimes and rules.

In conclusion. Rome does not pay traitors because it does not reward those who only know how to break systems—only those who can run them. María Corina Machado was useful during a phase of pressure and delegitimization, but the transition designed by Washington requires continuity, control, and predictability—assets embodied by Delcy Rodríguez.

In that sense, Venezuela confirms a new rule of empire: loyalty to destabilization buys attention, but only governability earns survival.

What We’re Watching 🔎 . . .

EU Set to Sign Historic South America Trade Deal Despite French Opposition [link]

Lyubov Pronina, Donato Paolo Mancini, and Andrea Palasciano, Bloomberg

The European Union has cleared the political hurdle to sign its long-delayed free-trade agreement with Mercosur next week in Paraguay, creating an integrated market of 780 million consumers and marking the bloc’s largest trade pact to date. While the projected economic impact is modest, the strategic significance is not. The deal strengthens Europe’s footprint in South America at a moment when China has emerged as the region’s dominant industrial supplier and commodities buyer. After more than two decades of negotiations, EU leaders are framing the agreement as a statement of strategic sovereignty and an instrument to diversify trade amid growing global protectionism.

The path forward remains politically sensitive. Opposition from major farming countries, led by France and initially Italy, exposed deep tensions between free trade ambitions and domestic agricultural protection. Rome’s late shift, aided by safeguard mechanisms and budget concessions, unlocked consensus, but resistance persists and parliamentary approval is still required. What bears watching now is implementation: how quickly safeguards are triggered, whether environmental and regulatory commitments are enforced, and if this agreement becomes a model for Europe’s broader response to U.S. tariffs and intensifying competition with China.

Venezuela Leaders Free Political Prisoners in a Sign of Possible Change [link]

Jack Nicas, Emma Bubola, Emiliano Rodríguez Mega, and Genevieve Glatsky, The New York Times

Venezuela’s interim authorities have begun releasing political prisoners in what appears to be the first tangible gesture since Nicolás Maduro’s capture and removal. While only a handful of releases were confirmed by Thursday night, including prominent security analyst Rocío San Miguel and several foreign nationals, the announcement carries symbolic weight. It signals an attempt by the Rodríguez-led interim government to ease international pressure and test a narrative of reconciliation, even as the broader repressive apparatus remains intact. For Washington, the move aligns with Marco Rubio’s stated three-phase plan of stabilization, reconciliation, and eventual transition.

Still, caution dominates the reaction. Venezuela has a long history of pairing limited prisoner releases with intensified repression elsewhere, and hundreds of political detainees remain behind bars. Families waiting outside El Helicoide and Rodeo prisons underscore the gap between announcements and outcomes. The key question is whether this marks the start of systematic dismantling of repression, or another tactical pause designed to buy time, legitimacy, and negotiating leverage under U.S. oversight.