- GCaM

- Posts

- Roads Diverge in the New World

Roads Diverge in the New World

Dear all,

We welcome you to the Greater Caribbean Monitor (GCaM).

In this issue, you will find:

Bukele’s Path Leads to Singapore...or Nicaragua

The New World’s Third Option

As always, please feel free to share GCaM with your friends and colleagues.

If you’ve been forwarded this newsletter, you may click here to subscribe.

Best,

The GCaM Team

Bukele’s Path Leads to Singapore...or Nicaragua

782 words | 4 minutes reading time

In 2024, President Nayib Bukele secured reelection by a wide margin, propelled by genuine and overwhelming popular support. That wave of support has also lifted his party, Nuevas Ideas, to a commanding supermajority in the legislature. The votes were real. The popularity is real. But so is the unchecked concentration of power.

Panorama. Recently, Bukele’s Legislative Assembly approved a sweeping constitutional amendment: presidential term limits were eliminated, presidential terms extended to six years, and run-off elections abolished.

When combined with the 2021 ruling by a Constitutional Court stacked with Bukele loyalists—which paved the way for his controversial reelection—the message is clear: Bukele now has a legal runway to remain in power indefinitely, with virtually no institutional counterweight.

The amendment is not an isolated event but the culmination of a broader process of institutional erosion: the subjugation of the judiciary, the militarization of public life, the normalization of emergency powers, and the systematic weakening of opposition forces.

Yes, But. The question is no longer about popularity or control—it’s about design. Can a leader with overwhelming public support govern without falling into the pitfalls of unchecked power? And more urgently: what kind of regime is El Salvador becoming?

The Asian Path. Bukele has never hidden his admiration for Singapore. In social media, his governing style has drawn frequent comparisons to its founding father, Lee Kuan Yew. The appeal is clear: a small country with a strong state, modern infrastructure, low crime, high growth—and tight political control.

Singapore is often cited as the textbook case of “authoritarian efficiency,” a system that traded political liberalism for order but delivered world-class governance, investor confidence, and global relevance. Today, it stands as one of the most prosperous nations on earth.

That’s the version of autocracy Bukele wants to sell. The new constitution is framed as a modernizing reform, and indefinite reelection as a path to stability. In his narrative, order is the prerequisite for progress—and he alone can deliver both.

But Singapore wasn’t built on charisma or fear—it was built on institutions: a competent bureaucracy, efficient courts, and a disciplined policy apparatus. Lee Kuan Yew’s regime repressed opposition, yes—but it also repressed corruption and improvisation, something Bukele has yet to replicate.

A Nearer Path. Closer to home, there’s another model: Daniel Ortega’s Nicaragua. Over time, Ortega dismantled democratic institutions, erased term limits, and concentrated power in the hands of his family. He neutralized the press, criminalized dissent, and turned elections into ritual theater. What he hasn’t managed to build—after nearly two decades in power—is a functional state.

Nicaragua is now an authoritarian regime with mediocre economic performance, persistent poverty, and zero institutional credibility. The state delivers control, not capacity. Ortega’s power survives not because he’s admired, but because he’s feared—and because there’s no one left to challenge him.

The comparison is uncomfortable, but increasingly relevant. El Salvador’s indefinite reelection, state of exception, media crackdowns, and growing personalization of power all mirror the early phases of Nicaragua’s descent.

If Bukele stays on this path, the shift from popular strongman to entrenched autocrat could come faster than expected—especially if he fails to deliver tangible prosperity alongside his crackdown on gangs.

What’s Next. By his own choice, Bukele has already crossed a pivotal threshold—the legal architecture for indefinite power is now in place. The judiciary is under his control, the political opposition is irrelevant, and public support remains high, fueled by a historic drop in homicides and the sense of long-awaited order.

Yet the future of El Salvador remains uncertain. The country could evolve into a disciplined, technocratic autocracy, credible enough to attract long-term investment and international partnerships. A Latin American Singapore.

But for that to happen, Bukele would have to do something rare among powerful men: bind himself to rules. That means ending the state of exception, restoring due process, ensuring judicial independence, and limiting discretionary power in economic governance.

Otherwise, the logic of power will take its usual course—toward greater repression, improvisation, and isolation. And El Salvador will drift, slowly but surely, into the orbit of Ortega’s Nicaragua: a regime feared abroad, stagnant at home, and condemned to decline.

Bottom Line. Bukele’s case—and his overwhelming popularity—is echoing across the region. In a context where populations are increasingly disillusioned with the principles of liberal democracy—largely due to a palpable lack of results—he is rapidly turning authoritarianism into a development brand.

But Latin America is no stranger to strongmen. If history—and even Singapore—has taught us anything, it’s that more than strongmen, the region needs strong states.

The world is watching closely, because the implications reach far beyond El Salvador. Bukele’s rise feels like an urgent test for the liberal democratic model in Latin America—and perhaps globally.

What happens in the coming years will serve as a powerful example, an enticing answer to the dilemma between prosperity and decline.

The New World’s Third Option

794 words | 4 minutes reading time

Amid the escalating U.S.–China trade rivalry, the European Union (EU) and Latin America and the Caribbean face the same strategic dilemma: navigating between two superpowers they both depend on or redefining their own path.

Panorama. Historically, the EU’s presence in the region has been shaped by development aid, with approximately EUR 3 billion being disbursed between 2021 and 2027, primarily for social and development programs, with very little involvement in strategic sectors such as energy and infrastructure—a space that has been largely taken up by China.

Now, with supply chain security, critical raw materials, and technological sovereignty at stake, Brussels must pivot from aid donor to strategic partner—a shift made more urgent by the tariff-driven disruptions of Donald Trump’s trade agenda.

China is the region’s second-largest trading partner, purchasing 34% of raw material exports and financing major infrastructure projects—including the USD 4 billion Chancay port in Peru—alongside commodity contracts with Brazil, Colombia, and Chile to consolidate control over critical resources.

The EU aims to counter this with trade pacts covering 95% of the region’s GDP — including the pending two-year EU–Mercosur agreement — and EUR 45 billion in Global Gateway investments, with more than 130 projects over four years focused on lithium, renewable energy, green hydrogen, transport, health, and digital networks.

Economic Outlook. The EU–Mercosur agreement would link a market of 770 million people with a combined GDP of EUR 18 trillion, strengthening resilience, reducing dependence on Chinese inputs, and diversifying supply chains. This builds on the EU’s position as Latin America’s third-largest trading partner—after the U.S. and China— with total goods and services trade reaching EUR 395 billion. Together, the two regions account for 20% of global GDP and 10% of the world’s population.

Trade flows could grow by 37% under current terms; with deeper integration measures —cross-cumulation of rules of origin and Mutual Recognition Agreements—the increase could reach 70%, while boosting intra-regional trade by up to 38%.

Notably, 25 of the EU’s 34 officially listed critical raw materials are sourced from the region, underscoring its pivotal role in driving Europe’s green and digital transition.

Access to EU technology and investment can help Latin American economies move up the value chain, fostering renewable energy, agri-tech, and advanced manufacturing sectors.

Geopolitical Stakes. The U.S.–China rivalry has turned Latin America and the Caribbean into a very contested ground. In just two decades, China has risen from a marginal player to a dominant force, and by 2035 could overtake the U.S. as its top trading partner.

As pressure to choose sides grows, “strategic non-alignment” becomes harder, creating an opportunity for the EU to position itself as a third pole—offering partnership without zero-sum demands.

Beijing is now Mercosur’s main trading partner—the destination for 29% of exports and the source of 25% of imports—and has deepened its presence through the Belt and Road Initiative and the China–CELAC forum.

Beyond economics, Europe must move past its paternalistic stance and engage Latin America as a strategic Atlantic partner in security. Even though it accounts for only 2.4% of global defense spending, the region controls strategic routes such as the Magellan Strait and Drake Passage—crucial if the Panama Canal or Northwest Passage are disrupted—making its stability a vital

Why It Matters. A sharp shift in this direction would move beyond a donor–recipient dynamic toward a partnership grounded in reciprocity and mutual benefit, leveraging historical, cultural, and linguistic ties—such as the Iberoamérica connection—that neither Washington nor Beijing can replicate.

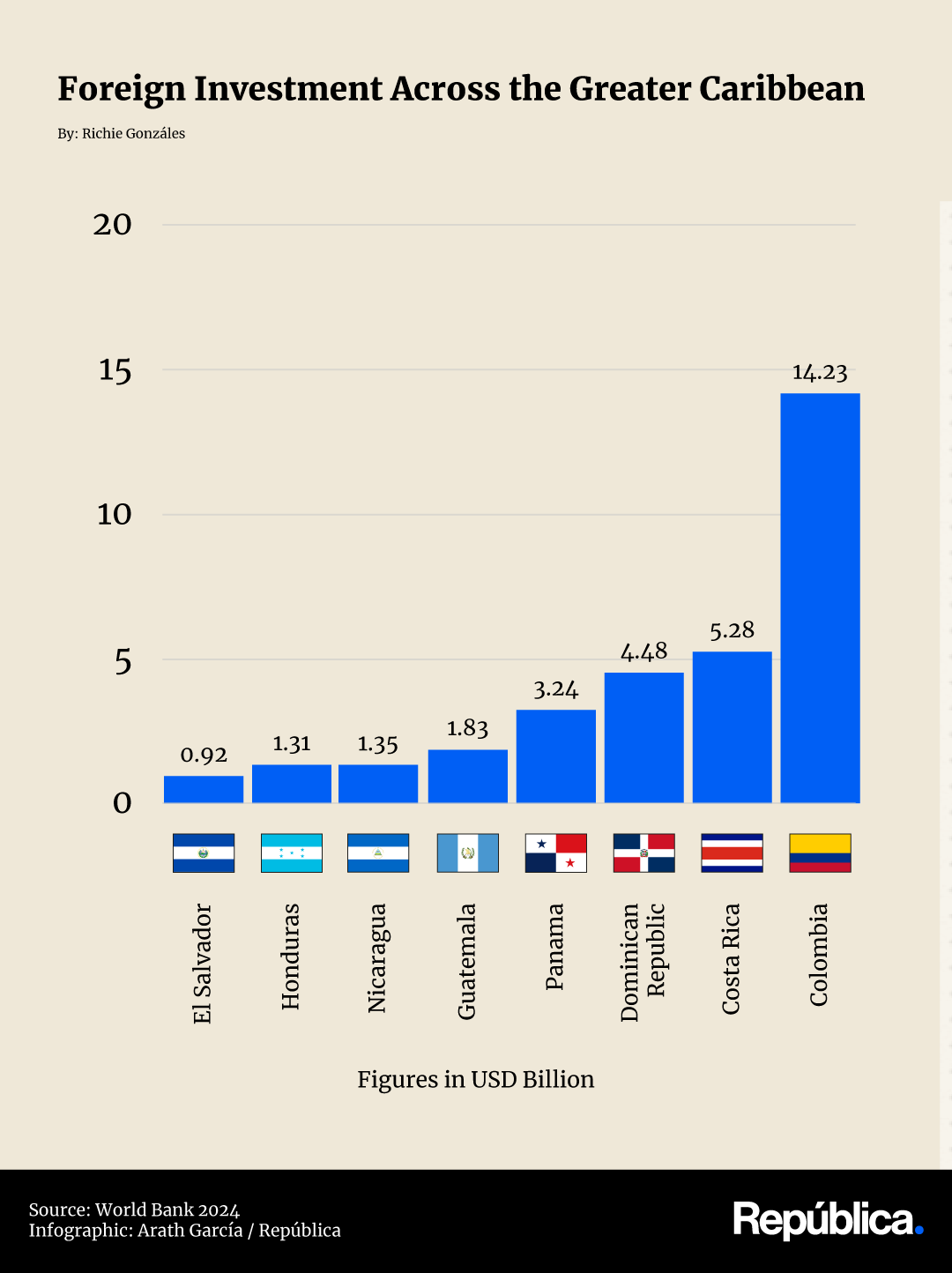

Despite macroeconomic stability, the region’s growth remains insufficient to reduce poverty or meet labor demand, with the EU’s share of investment at just 15% — its lowest since 2012.

Under Trump, the U.S. is likely to maintain pressure through restrictive trade deals aimed at isolating China, prompting both regions to pursue greater economic autonomy.

As neither Latin America nor the EU are perceived as direct rivals or significant threats by the U.S. or China, their cooperation offers not only a logical path to diversification but also a safeguard for their security through a pragmatic approach to the trade war

What’s Next. Turning this strategic reset into a lasting reality will require more than agreements — it demands a shift in mindset from both sides, where the two regions stand to gain: the EU would access a market of 1.1 billion people and secure raw materials such as copper and silicon, while Latin America would attract investment to spur growth and create jobs for its young, expanding workforce amid shrinking U.S. migration options.

Accelerating flagship Global Gateway projects—from green hydrogen corridors to secure digital networks—will showcase the partnership’s value and credibility.

Coordinated diplomacy and joint positions in global forums could strengthen both blocs’ influence in shaping trade rules, climate policies, and digital governance.

Above all, time is short: in a world where the gravitational pull of Washington and Beijing grows stronger, the window for shaping a truly autonomous EU–Latin America alliance is narrowing.

What We’re Watching 🔎 . . .

Trump administration eyes military action against some cartels [link]

Idrees Ali, Reuters

Washington is moving from rhetoric to operational planning on cartels. After designating Mexico’s Sinaloa and other cartels—plus Venezuela’s Tren de Aragua—as global terrorist organizations in February, the Trump administration has directed the Pentagon to develop options that could include U.S. Navy interdictions at sea and targeted raids; Secretary of State Marco Rubio says the new framework enables use of Defense and intelligence assets against these groups.

Mexico’s President Claudia Sheinbaum insists no U.S. troops will enter Mexican territory, and U.S. officials say action is not imminent, but the policy shift reframes cartel suppression as counterterrorism. For Latin America, that widens authorities for surveillance, maritime stops, and cross-border pursuits—raising sovereignty frictions with Mexico and complicating security cooperation across the Caribbean corridor. Near-term ripple effects in compliance and logistics (more scrutiny of port calls and carriers) and political blowback across the region are expected if operations proceed.