- GCaM

- Posts

- Fear and Loathing in Latin America

Fear and Loathing in Latin America

Dear all,

We welcome you to the Greater Caribbean Monitor (GCaM).

In this issue, you will find:

Why Latin America Can’t Ignore Its Union Problem

Argentina's Left Without a Kirchner

A Return to Colombia’s Dark Past

As always, please feel free to share GCaM with your friends and colleagues.

If you’ve been forwarded this newsletter, you may click here to subscribe.

Best,

The GCaM Team

Why Latin America Can’t Ignore Its Union Problem

853 words | 4 minutes reading time

The recent Chiquita crisis in Panama is more than a labor dispute—it underscores the recurring failure of coordination among unions, corporations, and government authorities, where disjointed and often reactive responses leave all parties worse off.

The incident reveals deeper structural tensions within Latin America’s vital agroindustrial sector—a domain where labor, law, and competing interests within unions, corporations, and politicians frequently collide.

Panorama. The crisis was triggered by the enactment of Panama’s Law 462, a pension reform that raised the retirement age for agroindustrial workers. In response, thousands of banana workers staged a strike—not against Chiquita, but in protest of the government’s decision.

Citing $75 million in losses and a court ruling that declared the strike illegal, Chiquita responded by dismissing nearly 7,000 workers and suspending operations in Bocas del Toro, Panama’s key banana-producing region.

According to César Guerra—subcoordinator of COLSIBA, the regional union federation to which SITRAIBANA, the leading union behind the Chiquita strike, belongs—the walkout was a response to years of exhaustion and stagnant working conditions that the Panamanian government had long neglected.

While Guerra acknowledged the growing economic toll of the strike, he defended the union’s right to organize it. Though a resolution may already be overdue, he maintains that a negotiated solution between the company, the union, and the government is both possible and necessary to preserve jobs.

Looking Back. This is far from the first time that union-led escalation has destabilized a major agroindustrial operation in Latin America. The region’s banana industry has repeatedly witnessed labor actions—at times justified, at others excessive—that have precipitated corporate exits, bankruptcies, or episodes of violent repression.

In 1954, Honduras experienced a major upheaval when approximately 40,000 workers brought operations at United Fruit and Standard Fruit to a halt. While the strike yielded important concessions, it also compelled both companies to reconsider their long-term presence in the country, ultimately resulting in a gradual withdrawal from direct operations.

Colombia also became a focal point of conflict during the 1980s and 1990s in the Urabá region. Several union leaders with ties to leftist guerrilla movements died in clashes involving military and paramilitary forces, fueling widespread insecurity and prompting many banana companies to withdraw their operations from the area altogether.

In most of these cases throughout history, the pattern is clear:a powerful labor front applies pressure, governments struggle to respond, and companies either concede or exit.

Contrast. While there are many reasons why unions have historically been a contentious issue in Latin America, weak or poorly designed labor laws and regulatory frameworks stand out as a particularly significant factor. For example, the contrast in labor dynamics between Latin America and the United States is striking.

In the U.S., unions operate under strict legal frameworks that regulate strikes, collective bargaining, and labor elections. Unions in Latin America often have the capacity to organize sweeping sector-wide shutdowns with minimal legal restraint or effective state intervention, making labor conflicts more abrupt and disruptive.

Moreover, unions in the region frequently align with leftist parties or international labor NGOs, amplifying their political capital. In the U.S., unions are more institutionalized and face legal hurdles when engaging in political advocacy.

As Guerra puts it: “There are tax havens, but also labor havens—places where multinationals operate with few checks on compliance.” But the reverse is also true: there are labor environments where unions wield disproportionate influence over public and corporate outcomes.

Regional Echoes. Panama’s crisis is sending shockwaves across neighboring countries, raising concerns in a region that dominates the global banana export market.

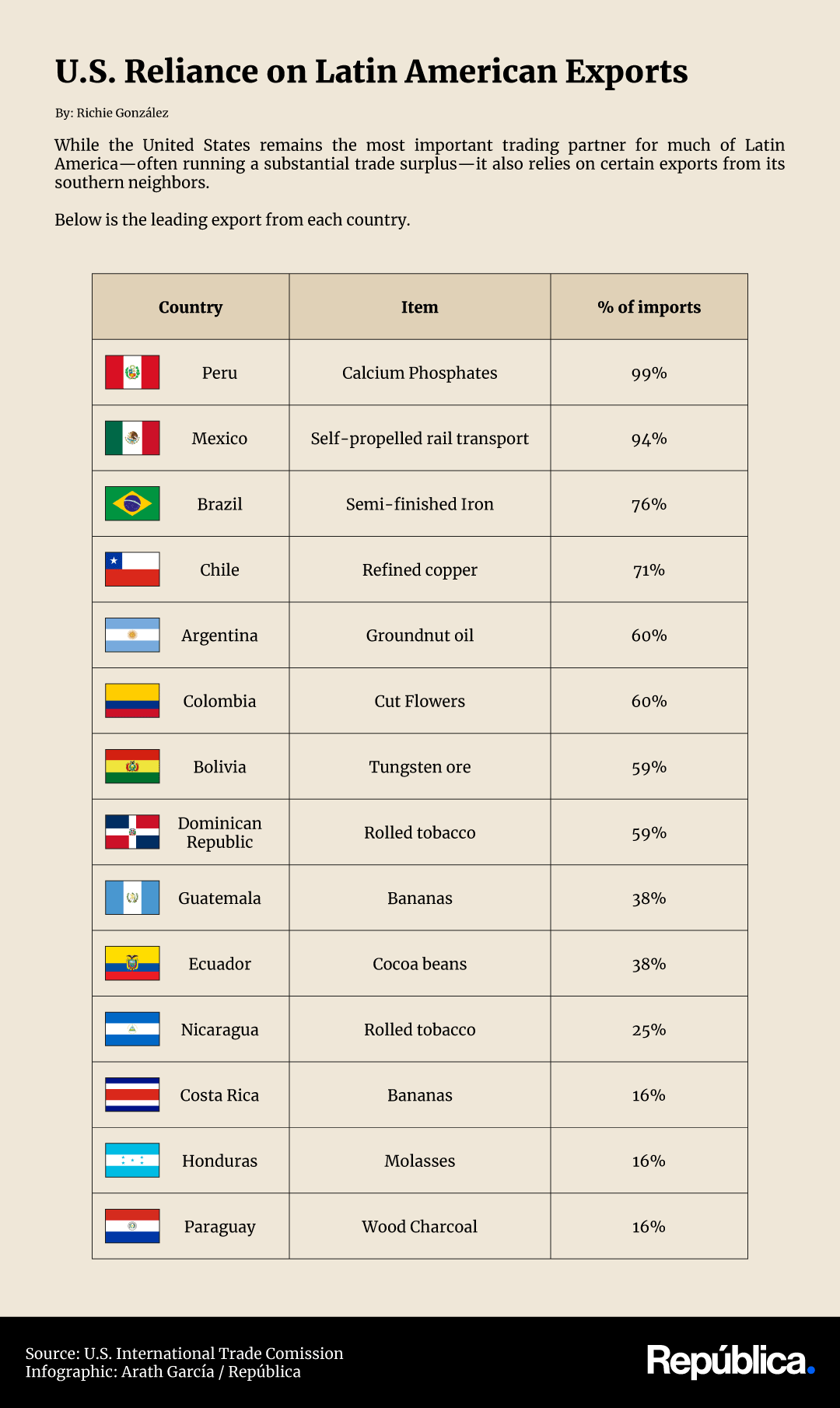

Latin America is home to the banana industry's most influential producers—Ecuador, Costa Rica, Guatemala, and Colombia—which collectively account for more than half of global banana exports, generating over $9 billion in annual income for the region.

Ecuador, now the world’s leading banana exporter, has maintained a long-standing resistance to unionization—a stance that, while often criticized, has contributed to a more predictable and stable environment for multinational companies. As a result, several firms that faced persistent labor unrest in other countries have shifted operations there.

Guatemala, on the other hand, has long grappled with a deeply flawed pension system—raising concerns among both agroindustrial employers and unions. The state, in its capacity as an employer, holds a historic debt of more than $9.46 billion, a burden that has led to slow and cumbersome administrative processes and inadequate pension payouts.

Bottom Line. Bananas may be at the center of the current crisis, but they represent just one thread in the fabric of Latin America’s broader agroindustrial economy that sustains millions of rural livelihoods.

Unions in the region often emerge in response to real grievances, like unsafe working conditions and state inaction. But without effective legal boundaries or reliable mechanisms for dispute resolution, their influence can morph into unchecked power.

When confrontation replaces negotiation as the default mode of labor engagement, the result is a cycle in which everyone loses workers, businesses, and national economies alike.

To safeguard the future of this critical sector, Latin America must move beyond reactive crisis management. Otherwise, the region's agroindustrial backbone will remain exposed, not only to global market pressures, but to self-inflicted wounds that no economy can afford.

Argentina's Left Without a Kirchner

504 words | 2 minutes reading time

Former Argentine President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner has been sentenced to six years of house arrest, leaving the country’s political left without its most influential figure just months ahead of the October elections.

Context. Fernández de Kirchner (CFK) had been under investigation since 2018 for awarding public works contracts in Patagonia to companies linked to close associates during her presidency, causing an estimated loss of USD 1 billion to the state. In December 2022, she was convicted of fraud and sentenced to six years of imprisonment along with a lifetime ban from holding public office.

Following a lengthy appeals process, Argentina’s Supreme Court upheld the conviction on June 10, rejecting all arguments presented by the defense.

Given her advanced age, CFK will serve her sentence under house arrest.

The court’s decision marks a watershed moment in the contemporary history of Peronism.

Why it Matters. Cristina Kirchner has been the dominant figure of Peronism in the 21st century. Her disqualification ends a political career that—though already weakened—now forces a structural redefinition of the Argentine left. As First Lady, senator, president, and vice president—where she effectively wielded power behind Alberto Fernández—she was the central strategist and leader of the movement.

Her conviction comes during a critical election year.

In the recent legislative elections in Buenos Aires (CABA), Peronism came in second, ahead of the PRO party led by Mayor Jorge Macri.

However, the major winner was Javier Milei’s La Libertad Avanza (LLA), which secured a strong lead. Combined, LLA and PRO obtained 45% of the vote, while Unión por la Patria (UxP), led by Kirchner, secured just 27.5%.

Yes, but. Peronism now faces the challenge—or opportunity—of reuniting factions long divided under CFK’s leadership. Nevertheless, the legacy of Néstor and Cristina Kirchner remains a political current in its own right. The Justicialist Party, Kirchnerism, and "non-K Peronism" will now vie to control the coalition.

Despite the movement’s current weakness, figures such as Buenos Aires Governor Axel Kicillof—largely responsible for Peronism’s second-place finish in CABA—are gaining traction.

However, as a prominent Kirchner ally, Kicillof must distance himself from her legacy if he hopes to expand his appeal beyond the capital.

Meanwhile, figures like Máximo Kirchner (Cristina’s son), Agustín Rossi, and Sergio Massa are all maneuvering for leadership within the Kirchnerist faction. But unity remains distant.

What to Watch. The left must now decide whether to rally behind a new leadership or fall into infighting between Kirchner loyalists and her detractors. For now, Peronism is more adrift than ever. As it searches for a new leader, the political right continues to consolidate around President Javier Milei.

LLA has outperformed PRO in its own strongholds, and the Macri family’s political capital continues to erode, forcing them closer to Milei ahead of the October legislative elections.

Time is short. With just four months to go, the right is not only more united—it is also stronger.

While UxP may benefit from CFK’s exit, internal fractures and the weight of her conviction continue to weaken the left’s ability to challenge Milei’s rising power.

A Return to Colombia’s Dark Past

452 words | 3 minutes reading time

After decades of relative calm, political violence has resurfaced in Colombia—this time under the stewardship of a left-wing government.

The country was shaken by the attempted assassination of Senator Miguel Uribe Turbay, a leading figure of the opposition and presidential hopeful for the right-leaning Centro Democrático party, founded by former President Álvaro Uribe.

What Happened. Uribe Turbay was shot during a campaign speech, struck twice—one bullet hitting his head.

His condition is critical, with doctors describing his survival thus far as “miraculous.” Videos of the attack show the senator being shot at point-blank range.

The assailant, a 14-year-old boy, was apprehended by Uribe’s security team. Authorities suspect at least two more individuals were involved in what is being treated as an attempted political assassination.

Context. The attack comes amid growing political tensions. Just two days prior, President Gustavo Petro publicly disparaged Uribe Turbay on X, referencing his family lineage: “My God! The grandson of a president who ordered the torture of 10,000 Colombians speaking of institutional rupture?” The comment referred to former President Julio César Turbay, Uribe’s grandfather.

Observers in Colombia argue that Petro’s confrontational rhetoric has exacerbated polarization and radicalization, contributing to an atmosphere ripe for political violence.

Conversations retrieved from the attacker’s phone suggest the operation was rushed, with one message urging, “It has to be today, whatever the time.”

A Troubling Pattern. Uribe joins a grim list of presidential candidates in the Americas targeted in recent years—Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil, Fernando Villavicencio in Ecuador, Donald Trump in the United States—all right-wing figures known for opposing leftist establishments. Of them, only Villavicencio did not survive.

Despite international narratives often framing political radicalism as a phenomenon of the right, it is right-wing candidates who have increasingly become targets of violence.

The story also carries historical weight. Uribe Turbay is the son of Diana Turbay—daughter of former President Julio César Turbay—who was kidnapped and killed in 1991 by a Marxist guerrilla group acting under orders from Pablo Escobar.

Why It Matters. This attack raises fears of a return to Colombia’s darkest era—the days of guerrilla insurgencies and drug cartel terror.

Former Senator Juan Manuel Galán, whose father Luis Carlos Galán was assassinated by the Medellín cartel in 1989, urged President Petro to “de-escalate the political discourse” that many view as fueling current unrest.

Though Petro condemned the attack, he drew backlash for defending the teenage gunman, stating, “The first duty of the State is to protect the life of the minor.”

As Uribe Turbay clings to life, Colombia’s road to the 2026 elections—where the left faces an uphill battle—has been stained with blood and fear. For many, the Petro experiment marks a chilling throwback to the violence of the 1980s and 1990s.

What We’re Watching 🔎 . . .

Brazil plans panda bond as Lula looks to bolster ties with China [link]

Michael Pooler y Michael Stott, Financial Times

Brazil is preparing to issue its first sovereign bonds denominated in Chinese yuan—so-called "panda bonds"—with an estimated value between USD 200 million and USD 300 million. T

he move aims to strengthen ties with China, its largest trading partner, and attract Asian capital in the wake of President Lula’s recent visit to Beijing. The initiative is part of a broader financing strategy that includes new issuances of sustainable dollar bonds and a potential return to the euro-denominated debt market, running parallel to ongoing negotiations over the MERCOSUR–EU trade agreement.

However, the plan faces skepticism amid the government’s expansionary fiscal policy, which has pushed the nominal deficit to 7.8% of GDP and kept interest rates elevated at 14.75%. While Brasília is targeting an investment-grade credit rating by 2026, concerns remain about its fiscal sustainability, particularly in a pre-election context marked by growing pressure for increased social spending.

U.S. and China Spar for Influence on the Paraguay-Paraná River System [link]

Gregory Ross, Americas Quarterly

Spanning over 3,400 kilometers and linking Brazil, Bolivia, Paraguay, Argentina, and Uruguay to the Atlantic Ocean, the Paraguay-Paraná river system is emerging as a strategic corridor at the heart of a quiet struggle for influence between the United States and China.

This vital commercial artery moves more than 100 million tons of goods annually—including soy, corn, lithium, natural gas, and copper—and could supply up to 40% of the world’s grain by 2030.

After years of underinvestment and the growing toll of severe droughts—causing losses of over USD 300 million in Paraguay alone in 2023—both powers are ramping up efforts to shape the future of the river corridor. China is consolidating its foothold through infrastructure projects such as the Chancay port in Peru and key tenders like dredging operations in Argentina. Meanwhile, the United States is reinforcing its position with technical assistance from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, financing from the Development Finance Corporation (DFC), and enhanced counternarcotics cooperation.