- GCaM

- Posts

- Cuba will fall next... but how?

Cuba will fall next... but how?

Dear all,

We welcome you to the Greater Caribbean Monitor (GCaM), the last of the year.

Although Venezuela has drawn most of our attention in recent months, it is important to note that it is not the only relevant country in the Greater Caribbean. Cuba remains a long-forgotten front of resistance in the Western Hemisphere, largely because the regime has rendered the country increasingly irrelevant by dismantling nearly every productive capacity it once had. But it should not be forgotten—because neither Trump nor Rubio will—that it remains a stronghold of human rights violations and espionage, as well as a gateway for enemies of the free world.

Today, however, the Castro-era regime is closer to collapse than at any point since the fall of the Soviet Union. The central question is whether it will indeed fall—and if so, when. That is the question we aim to address today, and one that will return repeatedly throughout the year. We appreciate your trust in us—as you did with Venezuela—through the long and uncertain process of unfolding events.

In this issue, you will find:

Cuba is Next on Marco Rubio’s Hit List

Who Will Miss Maduro the Most?

Europe Joins the Party Late, But Wins Big Time

As always, please feel free to share GCaM with your friends and colleagues. We wish you a strong start to 2026.

If you’ve been forwarded this newsletter, you may click here to subscribe.

Kind regards,

Cuba is Next on Marco Rubio’s Hit List

934 words | 5 minutes reading time

Cuba is entering 2026 with fewer external cushions, a worsening energy crunch, and a U.S. policy team that views “managed collapse” as a feature, not a bug.

In perspective. For Washington, Cuba has always been more than an anachronistic dictatorship 90 miles from Florida. It is a migration valve, an intelligence and influence platform for U.S. rivals, and a symbolic prize in U.S. domestic politics—especially in Florida. That mix is why Cuba tends to reappear whenever a U.S. administration wants to demonstrate hemispheric resolve.

The difference now is timing. The island is already strained by structural decay with chronic blackouts, fuel scarcity, and an economy that has not recovered from its post-pandemic shock.

Against that backdrop, new U.S. pressure stops being about “nudging reform” and becomes more about forcing a decision point.

Cuban anxieties about a “siege scenario” were reported this week as Venezuelan fuel flows fall off and the island’s limited alternatives become politically risky for would-be suppliers.

Why Cuba matters. Marco Rubio’s posture on Cuba is not ambiguous. He has built a career treating the survival of castrismo as an unacceptable outcome and framing the regime as a security threat rather than a mere human-rights problem. Politically, that stance maps cleanly onto Florida incentives. Strategically, it fits a broader line, with Cuba as a node that enables malign networks that go from intelligence cooperation to illicit finances, and the export of repression know-how.

What changes the equation is Cuba’s historical dependence model. The revolution was propped up by Soviet subsidies; after the USSR’s collapse, Havana endured the “Special Period” because the external patron vanished.

In the 2000s, Venezuela became the substitute patron via preferential oil flows and political alignment. If that lifeline is now interrupted—whether by Venezuela’s own constraints or by U.S. interdiction leverage—Cuba returns to its older problem.

It does not have an affordable, reliable energy patron capable of underwriting the regime’s daily functioning at scale. Venezuela was Cuba’s largest supplier in 2025 and those cargoes have effectively fallen off as U.S. pressure constrains flows.

Between the lines. Trump has publicly leaned into the energy lever, saying he wants to stop Venezuelan oil and money from reaching Cuba and urging Havana to “make a deal” with Washington. This matters because it defines the bargaining chip. In this context, fuel scarcity becomes a coercive instrument, not simply a humanitarian tragedy. It also clarifies the administration’s likely sequencing: first, tighten the constraint; second, offer an “off-ramp” framed as Cuba’s choice.

The broader context of U.S. escalatory rhetoric in the region reinforces that logic.

Reporting in recent weeks has described a sharper U.S. posture in the Caribbean theater, including strikes and a widened counter-narcotics framing.

Even where Cuba is not the direct target, the message is deterrence through unpredictability.

On the lookout. The first and most likely scenario is reaching a deal under duress that, instead of following the logic of a democratic breakthrough, is a survival negotiation. The Cuban leadership could pursue limited concessions in areas like migration cooperation, selective releases, narrow market openings, and confidence-building measures on security in exchange for a structured energy and financial breathing space. It would resemble a transactional détente rather than regime change. The key variable is whether Washington demands symbolic capitulation or accepts incremental compliance that can be sold domestically as a win.

Scenario 2 would be “squeeze, then fracture.” If fuel scarcity becomes acute, governance fails first at the margins. For the regime, that would mean prolonged power cuts, food supply disruptions, and internal security stress.

The regime’s core question would shift from legitimacy to cohesion. At that point, elite conflict becomes plausible. Not necessarily a popular revolution, but a split between those who want to negotiate and those who prefer repression plus external defiance. This is the classical scheme of a revolution ignition according to political science tradition.

This path, however, is high-risk because it can trigger mass migration and unpredictable violence. Widespread anxiety about “catastrophic” conditions if supplies go to zero underscores why this scenario cannot be dismissed.

Yes, but. There is a third and not-so-nice-for-Trump scenario, and it involves Mexico, Russia or other non-aligned countries providing partial relief to the regime. Cuba may try to patch the gap with limited inflows from sympathetic partners. But the constraint is not only availability but also willingness to absorb U.S. retaliation. Mexico is a potential limited exception and Russia is another constrained option, while emphasizing that large-scale rescue is not evident.

This scenario stabilizes the regime just enough to prolong the stalemate, while the population continues paying the cost.

However possible, it is less likely. Actions on Venezuela are indirectly a threat to Sheinbaum, who knows Trump has already flirted with military intervention in the neighboring country.

Putin, on the other hand, has faced the harsh reality of Trump not complying with his wishes—as people were led to believe would not be the case—and being on his good side is crucial for the fate of his Ukrainian ambitions.

In conclusion. Rubio’s Cuba file is converging with Trump’s preferred instrument: coercive leverage, marketed as decisive strength. The island’s vulnerability is logistical, not only ideological. Without a dependable patron to cover energy and hard-currency gaps, Havana’s room for maneuver shrinks dramatically. The most plausible end state is a negotiated arrangement shaped by U.S. terms and Cuban survival instincts, not a clean democratic transition, similar to what we see in Venezuela today.

The danger is that if Washington overplays the squeeze—treating humanitarian breakdown as acceptable collateral—Cuba becomes less a controlled pressure campaign and more a trigger for regional instability via migration, security spillovers, and a chaotic succession fight.

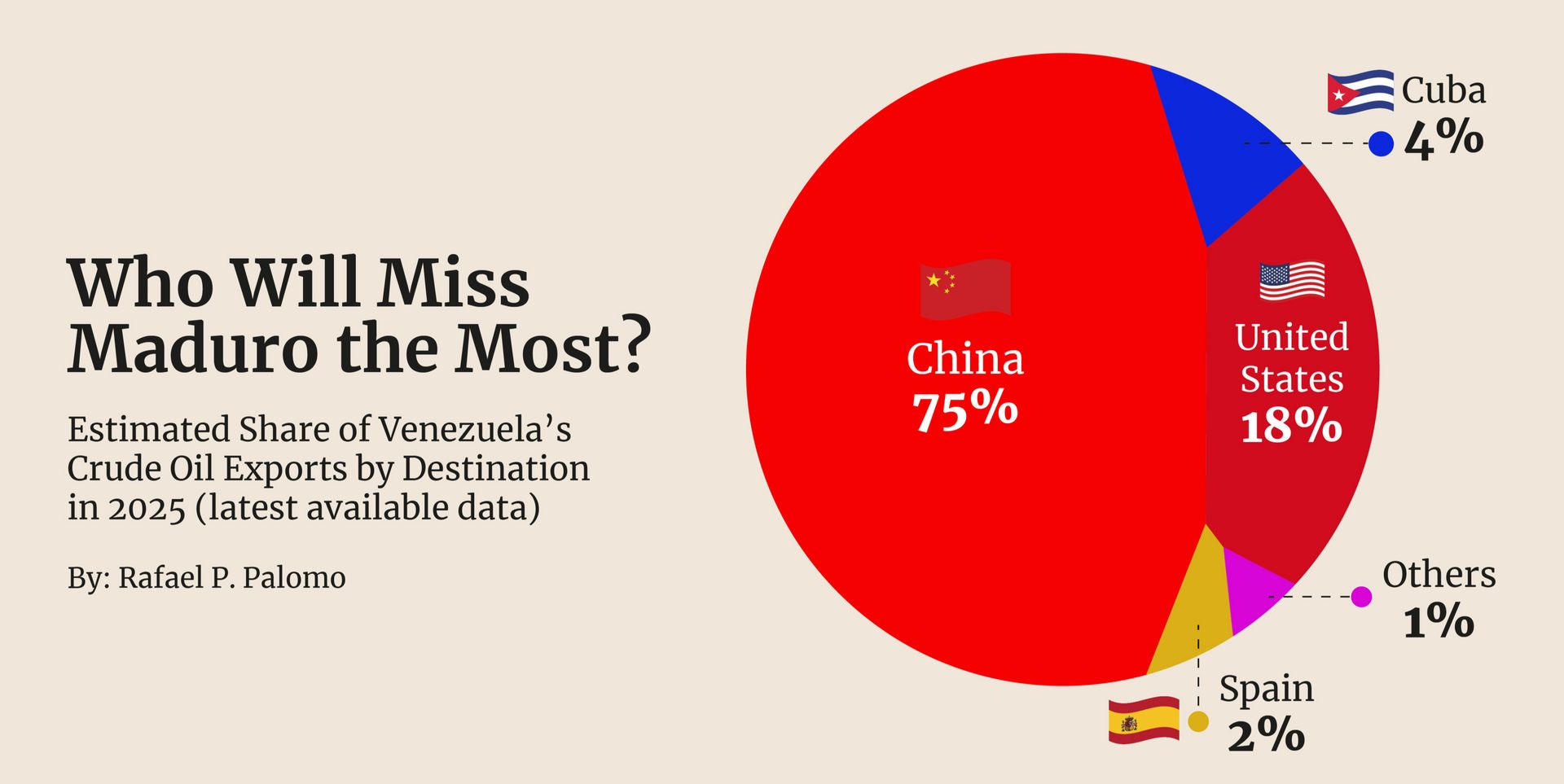

Maduro’s downfall reshuffles winners and losers less through barrels than through leverage.

In perspective. The United States “wins” not because Venezuelan crude suddenly becomes a decisive input to U.S. energy security, but because Washington cuts the regime’s external oxygen and forces a redistribution of risk across its adversaries. The graph captures the core imbalance: in 2025, China absorbed the dominant share of Venezuela’s crude exports (75%), while the U.S. took 18% and Cuba 4%, with the rest marginal.

In other words, the biggest immediate exposure to disruption is not in Houston; it is in Beijing—and, politically, in Havana.

The Dragon first. Start with China. Venezuelan oil has functioned as a sanctions-era workaround, with opaque intermediaries, indirect routing, and a steady flow that helps China diversify feedstock while pricing in the risk. In several months, the China-bound share of Venezuelan exports has been even higher than the estimate shown, once indirect flows are counted.

If Maduro’s fall translates into tighter U.S. control over licensing, shipping insurance, and enforcement, the immediate pain is not that China “runs out of oil,” but that one more reliable sanctions channel becomes uncertain, contested, and conditional.

That matters because uncertainty is a tax, since it raises transaction costs, constrains refiners’ optionality, and forces Beijing to decide whether to bargain, reroute, or absorb losses.

The big hit. Cuba is the cleaner case because it is smaller, poorer, and structurally dependent. The point is not that 4% looks “big” globally; it is that a thin slice can be existential when your grid is already brittle. Venezuelan crude and fuel have long functioned as Cuba’s external subsidy, cushioning shortages and stabilizing electricity generation.

Even modest reductions translate into blackouts, transport paralysis, and political stress.

If Caracas becomes a U.S.-managed file—whether through a compliant successor, a constrained interim arrangement, or direct leverage over PDVSA logistics—Havana loses its last patron with scale.

Last, but not least. Spain and “others” are political footnotes in energy terms, but the symbolism is useful. Europe can posture, but it is not the stakeholder that gets to set terms. Cuba and China, by contrast, are the real losers because Venezuelan crude has been both a commodity and an instrument.

Venezuelan oil has long been a payment mechanism, a sanctions workaround, and a geopolitical glue for them.

Maduro’s fall weakens the financial and logistical circuitry that tied Caracas to Washington’s rivals, and it does so in a way that hits Cuba hardest because it has the least room to hedge.

In the post-Maduro balance sheet, America’s biggest dividend is not additional oil; it is the strategic depreciation of its enemies’ options.

Europe Joins the Party Late, But Wins Big Time

677 words | 3 minutes reading time

The EU–Mercosur treaty marks more than a long-delayed trade agreement; it signals Europe’s entry into a geoeconomic phase of global competition.

Geoeconomic shifts. As the United States securitizes commerce and China consolidates value chains, the European Union is moving to protect strategic autonomy through market access and rules. The deal reshapes Europe’s relationship with Mercosur while exposing deep internal fractures over how power is now exercised inside the Union. The treaty reflects Europe’s recalibration of its geoeconomic and securitization environment.

The turn in U.S. foreign economic policy toward the securitization of commerce forces Europe into a reactive stance. Pushed to loosen its old ally’s grip, securing food, energy, and raw materials has become central to preserving strategic autonomy.

By anchoring itself to Mercosur, the European Union reshapes market leadership in Latin America. The move subtly dilutes U.S. political primacy without open confrontation.

The agreement places Europe squarely into geoeconomic competition for key value chains. Arriving later than China and the United States, the EU compensates through scale, long-term market integration, and regulatory dominance.

Institutional coercion. The treaty advances less through consensus than through procedural leverage. Qualified Majority Voting (QMV) was used to assemble a population-weighted coalition of large and mid-sized states with shared industrial interests. The mechanism’s purpose is to override opposition from agro-sensitive countries. Cooperation among aligned interests has replaced unanimity with voting arithmetic.

QMV permits the agreement’s commercial core to take effect even as cooperation chapters still require national ratification. Economic impacts will materialize regardless, effectively bypassing parliaments that would reject the deal if put to a different vote.

This marks a rupture in the European Union’s consensus-seeking culture, re-signifying trade as geoeconomic statecraft.

The result is a winners-and-losers logic closer to the power politics associated with Donald Trump, rewriting how the EU plays the game.

Value-chain positioning. Europe’s interest in Latin America has converged around trade volume and leverage over strategic material inputs. The EU views Latin America as a supplier of critical goods: cheap and abundant food systems, key energy inputs, and access to raw materials. This responds to the need to stabilize European value chains while avoiding confrontation with the United States.

The treaty should considerably reduce exposure to supply shocks concentrated in Asia or geopolitically volatile regions.

By embedding itself in Mercosur, Europe gains regulatory and commercial influence over upstream segments of key value chains. Standards, certification, and market access become tools to shape production patterns rather than merely import outputs.

This strategy allows Europe to manage upstream segments without direct ownership, counterbalancing U.S. market dominance and China’s model of infrastructure-heavy capital deployment. Latin America becomes a contested geoeconomic space where control is exercised through bureaucracy and integration rather than force or finance.

Big winners, big losers. The treaty reshuffles political and economic payoffs on both sides of the Atlantic. Giorgia Meloni and Germany emerge as clear winners. Rome gains strategic relevance by spearheading the deal, while Berlin secures access to inputs critical for an expanding industrial and defense base fueled by rising military spending.

In South America, Lula da Silva and Javier Milei also benefit significantly. Lula advances a project he has pursued since his first term, while Milei leverages EU machinery imports alongside pragmatic cooperation with Washington.

The major loser is Emmanuel Macron, along with agro-industrial states such as Poland.

Domestic backlash from the agricultural sector heightens political instability, potentially strengthening Marine Le Pen—whose court appeal to run as a candidate may prove successful—and increasing the risk that trade-driven unrest accelerates a broader crisis of governance.

In conclusion. The EU–Mercosur treaty crystallizes a clear trade-off. Europe gains geopolitical positioning at the cost of consensus-based legitimacy. By stepping fully into geoeconomic power politics—amid heightened tensions tied to Trump’s eventual action on Greenland—the EU is now playing the world’s game rather than refereeing it.

The use of QMV as a coercive shortcut may prove effective in the short term, but it sets a precedent that can later be turned against those who deployed it first, eroding trust and stability inside the Union.

Strategic autonomy abroad comes with structural risks at home.